- Home

- Simon J. Knell

The Great Fossil Enigma

The Great Fossil Enigma Read online

LIFE OF THE PAST

James O. Farlow, editor

THE GREAT

FOSSIL ENIGMA

The Search for the Conodont Animal

SIMON J. KNELL

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington & Indianapolis

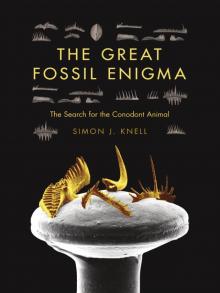

Illus., p. vi: Pinhead fossils. This scanning electron microscope image of conodont fossils on a dressmaking pin became an iconic image in those years after the animal had been discovered. Photo: Mark Purnell, University of Leicester.

This book is a publication of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47404–3797 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

© 2013 by Simon J. Knell

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1992.

Manufactured in the

United States of America

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Knell, Simon J.

The great fossil enigma : the search for the conodont animal / Simon J. Knell.

pages cm – (Life of the past)

Includes bibliographical references and

index.

ISBN 978-0-253-00604-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-253-00606-6 (ebook)

1. Conodonts. 2. Science – Social aspects. I. Title.

QE 899.2.C65K59 2012

562′.2 – dc23

2012016799

1 2 3 4 5 18 17 16 15 14 13

FOR THE

HARBINGERS OF SPRING

AND

ALL WHO WONDERED

Contents

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PRELUDE: THE IMPOSSIBLE ANIMAL

1 · THE ROAD TO EL DORADO

The fossil is found – the search begins – Pander's chicks – a friend of Murchison – Pander sees teeth and imagines fishes – others see trilobites, sea cucumbers – Owen sees anything but fish – Harley sees crustaceans – Moore in paleontological ecstasy – the fossil arrives in Cincinnati – Newberry sees fish – Grinnell misses Custer's Last Stand – Ulrich denies the fish and sees a worm – Hinde proves the fish – Smith's surprise – Huxley's encouragement – Zittel and Rohon murder the fish and see a worm.

2 · A BEACON IN THE BLACKNESS

Oil enters the American soul – fossils take on economic importance – microfossils take center stage – scientific worth of conodonts recognized – the black shales problem – godlike Ulrich vs. Kindle – Bryant's fishes – Hibbard's washing machine – Ulrich and Bassler's proof of method – Stauffer's chance discovery – Gunnell's vision of the future – Chalmer Cooper the disciple – Branson and Mehl's big campaign – Huddle's accidental beginnings – an index discovered – Icriodus the ideal – Cooper's cellophane fossils – contamination – Ellison's logic.

3 · THE ANIMAL WITH THREE HEADS

The fight for biological paleontology begins – Croneis's influence – the geography of thinking – Macfarlane's conodont oil theory – giant conodonts – Kirk finds bone – Gunnell's imaginings – Eichenberg's novel idea – Schmidt's assemblage – Stadtmüller's influence – Scott finds oil, earthquake and assemblage, and worm – Jones finds assemblages and Denham thinks of sex – Ulrich and Bassler in denial – Loomis and Pilsbry see snails – Demanet finds the fish – Cullison's remarkable jaw.

4. ANOTHER FINE MESS

Looking inside the fossil – chemistry like bone – Stauffer loses his teeth – Hass sees extraordinary detail – knowing the animal becomes impossible – more Ellison logic – Scott attempts to convince skeptics – Du Bois sees flesh – Germany plays catch up – Beckmann adopts German fish – Schmidt stuck in the past – Rhodes makes the assemblage a reality – a fine mess.

5. OUTLAWS

A chaos of names – the rights of nuts and bolts – Croneis's military order – the problematic Commission – Rhodes's duel with Sinclair – Lange's revolutionary worm teeth – Sylvester Bradley and Moore's parataxa – the solution to illegality is to change the law – the Treatise – Moore spells trouble – Arkell's ammonites join the cause – arguments get political – the plan is thrown out – Moore explains how to ignore the problem.

6. SPRING

Postwar optimism and the fifties generation – Rhodes's overview of the problem and the future – Müller's war – Gross's influence – Cooper pioneers acids – acids take hold and the conodont world is turned on its head – Beckmann's technique – Gross finishes off the dying fish – Schindewolf rises to power – the magic mountain – Müller in the Devonian – Beckmann reveals the German future – the rush for glory begins – Ziegler starts his meteoric rise – Müller escapes to the Carnic Alps – Walliser's energy – Lindström the schoolboy geologist – Sweet changes track and meets Bergström.

7. DIARY OF A FOSSIL FRUIT FLY

A fossil's evolution – Simpson's evolution – naive evolution – Haldane and Dobzhansky – New Paleontology – the problem of species – Müller's evolving fossils – Helms's evolutionary details – fruit flies – Ziegler's universal timescale – Ziegler begins global campaign – a little setback – the conodont becomes mainstream – the Pander Society formed – Müller's Cambrian exotica – Youngquist's Triassic proofs – the Cretaceous seems possible – Japanese Jurassic fossils – Mosher reveals fantasies – Gould and Eldridge deny conodonts’ evolutionary journey – Klapper and Johnson enter the fray – conodont workers march on regardless.

8. FEARS OF CIVIL WAR

Ziegler's mountain – Rhodes begins to construct the skeleton – Huckreide and Walliser do the same – Bergström and Sweet see skeletons too – Lindström's symmetry transitions – Rexroad and Nicoll's fused fossils – Bergström and Sweet take a stand – Schopf and Webers join them – Ziegler's world explodes – Lange's critical fossils – Pollock's clusters – Lane's symmetry – Kohut's numbers – arguing with Ziegler in Ohio – fears of fractricide – the Marburg peace accord – learning to speak a new language – Parataxa reappear – the “troublesome” Melville – Aldridge's diplomacy – Sweet's magnificent letter – Melville's astonishment – the turncoats.

9. THE PROMISED LAND

The promise of ecology – conodonts are like God – Rexroad's provinces – Lindström's honeymoon and Rosetta Stone – Sweet's great campaign – Bergström's Swedish American fossils – Bergström and Sweet's animal migrations – Schopf's models – Glenister and Klapper's Canning Basin – Druce in the field – Seddon's reef ecology – Seddon and Sweet's arrow worms – Druce's modifications – more problems for Ziegler – Merrill's changing ecology – the disruption of tectonic plates – Valentine's influence – Barnes and company put theory into practice – Waterloo – Jeppsson's seasonal migrations – rising doubts about ecology.

10. THE WITNESS

Catastrophism and color – Epstein acquires color vision – Alvarez and the asteroid – Schindewolf's extraterrestrial causes – Walliser's global events – Golden Spikes – MacLaren's asteroid – Clark's index of evolution – Fåhræus's ballet – Walliser joins a club – Kellwasser – Ziegler, Sa

ndberg, and Dreesen imagine another world – Jeppsson's island and his big idea.

11. THE BEAST OF BEAR GULCH

Man lands on the moon and the animal is found – the false dawn of Scott's blebs – Lange's mistake – Melton and Horner's fish – strange fossils – the Chicago sensation – the rumor of Scott's kidnap of Melton – Scott and Melton's friendship – getting funds – the truth of Melton – trouble brews – Huddle's doubts – closing ranks – publicity – writing up – Riedl's alternative – trouble in the quarry – Horner and Lower – East Lansing – news spreads of the discovery – yet more trouble – the paper disappears in a snow storm – errors in publication – thrilled readers and the indigestible meatball.

12. THE INVENTION OF LIFE

Models of animals – the purpose of the tiny fossils – Fahlbusch's algae and little victory – Nease's plants – Gross's animal-less conodont – Lindström's first animal – the rush for the S E M – Müller and Nogami's art – Lindström's tentacled worm – Rietschel's jaws – Lindström's grand thought experiment and tiny barrel – Conway Morris's conodont animal – denying Melton and Scott – Priddle looks to the lamprey – Bischoff introduces yet more animals – Hofker looks to the soil – Bengtson's new teeth – Landing's superteeth – Nicoll's filter – Hitchings, Ramsay, and Scott design filters – Jeppsson's teeth – Szaniawski's influential arrow worms.

13. EL DORADO

Finding the real animal – the shock of the old – Clarkson's puzzle – the Mazon Creek clue – meeting with Briggs – Halstead and the rumor – Aldridge's luck – the first paper – Aldridge joins up – Clark's extraordinary eye – rumors spread – the Conodont Animal – revisiting models – Dzik and Drygant remove the arrow worm – Janvier's critique – Nicoll's view – vandalism – the Waukesha animal – Nottingham – Smith strengthens the team – Norby's model – rebuilding the apparatus – separating fact from myth – strengthening interpretations – Dzik asserts the vertebrate – Tillier and Cuif's strange mollusks – Sweet's critique – Aldridge and Briggs's repost.

14. OVER THE MOUNTAINS OF THE MOON

The journey to the vertebrate – strange plants in the Cedarberg Mountains – Rickards's intervention – Aldridge's luck (again) – Theron's collaboration – African giants – Gabbott and Purnell strengthen the team – Gabbott's triumph – Kreja's helping hand – Moya Smith's expertise – Sansom's remarkable discovery – the conodont vertebrate becomes a reality – views of the fossil past are shaken – Purnell's bite – Briggs and Kear watch the dead – evidence continues to build – Donoghue's attention to detail – the animal becomes an alien – the vertebrate enters the grand narrative of life – a gathering storm – is this El Dorado after all?

AFTERWORD: THE PROGRESS OF TINY THINGS

NOTES

INDEX

Illustrations

Pinhead fossils.

1.1 Hinde's proof.

2.1 The solution to the black shales dispute.

3.1 Schmidt's fish.

3.2 Scott's conodont assemblages.

4.1 Hass's journey into the anatomy of the fossil.

5.1 Hass's compromise.

6.1 Walliser, Lindström, Ziegler, and Müller.

7.1 Helms's iconic evolutionary chart.

7.2 Müller's oddities.

8.1 Rexroad and Nicoll's fused conodont clusters.

8.2 Sweet and Bergström.

9.1 Modeling the ecology of the animal.

10.1 Fåhræus's choreography.

10.2 Jeppsson's oceanic models.

11.1 The beast of Bear Gulch.

12.1 Müller and Nogami's art.

12.2 Lindström's imagined animals.

12.3 Conway Morris's animal.

12.4 Conodont teeth.

12.5 Conodont filters.

13.1 The conodont animal.

14.1 Briggs and Aldridge.

14.2 Alien jaws.

14.3 The conodont animal as it is imagined today.

Preface & Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK HAS TWO BEGINNINGS. THE STORY OF THE “GREAT fossil enigma” begins with the Prelude. However for those expecting an analytical history of science, I suggest the afterword as a useful introduction because it explains how and why I have written this book and what lies beneath the narrative of the chapters. When I began this book in 2003, I envisaged it as the second in a trilogy of monographs revealing the fossil as a cultural object. In the first book, The Culture of English Geology, 1815–1851, I tried to show how fossils acted as cultural objects, shaping lives, playing a role in local politics, and leading to the founding of museums and the emergence of geology as a cultural field. As a museologist and cultural historian rather than a historian of science, I wanted to explain fossils and their place in society not in terms of a history of ideas but more holistically.

I took these ideas further in explorations of the politics of “English geology,” the possibilities of a cultural revolution in science, and cultural changes in geology in late-twentieth-century Britain. In this book, I turn my attention to the workings of a single community of researchers over a period of 150 years or so and consider how these men and women imagined and conceptualized the fossils that bound them together. Once again I have not attempted to write a straightforward history of ideas or to explore the contributions these fossils made to science in any detailed sense. My interest remains predominantly in culture, in the relationships between people, objects, and practices (the things people do, often formalized and institutionalized in some way). While I have long thought of this as a blend of cultural history and museology – as a branch of museum studies – I am aware that it is also a form of ethnology as it has long been understood in northern Europe (as a curiosity about one's own culture). No doubt it is this approach to the history of a science that caused a number of readers of the manuscript to consider it rather “strange.” If that is the case, I am delighted, for a study of this kind requires the author and reader to remove themselves sufficiently far from their subject to see the actions of individuals as strange rather than natural.

As I researched and wrote this book, I became increasingly aware that, as one of science's great enigmas, its subject already existed, though not in any coherent form, as a possession of all those who wondered about and worked on these fossils. If I began my research believing that I might be another user of these fossils, this time in my own analytical history, I soon understood that I had to prioritize the needs of those for whom the fossils already held meaning. Having never set out simply to tell a story, I came to understand that accessible narrative was critically important. Indeed, I felt it was an obligation. Consequently, I decided to put a good deal of my analysis into the afterword (which at various times I have considered an explanatory introduction) without making that part of the book oppressively long. I have written the narrative of the chapters broadly in chronological fashion, though some themes prevented me from adhering to this unwaveringly. I hope they retain something of the strangeness of my original outlook. I will leave the reader to decide whether he or she wants to stray into the afterword.

Finally, I should note that nowhere in this book do I assume the authority of a scientist. I am a historian. I listened to my actors and believed, as they did, in what they told me. Consequently, the animal appears in glimpses, as if through a mist. First it seems to be one thing then another, almost coming into view but then disappearing. For a long time the animal did not so much appear in the headlights of science as in its wing mirrors, implicitly present but shrouded in darkness.

Of course, books tend not to be read as they are written, and in the closing weeks before going to press, I became a little concerned that some readers might think that I am making a scientific argument, that I have a scientific opinion on the matters described in this book. I do not. I take no view on what is right or wrong, only in what is believed, and I have no preferred position regarding the biological attributes of the animal myself. I have been fascinated by all the various

manifestations of conodont animal, but scientists have to convince each other of the truth of their science, not me. It was inevitable, however, given the focus of this book, that I allocated considerable space to Melton and Scott's, Conway Morris's, and Clarkson and company's animals. Given the sensational significance of the latter, I am sure supporters and critics alike will recognize that British views on the animal have shaped the course of debate over the last thirty years and warrant detailed examination. In all three cases, those who possessed the conodont animal fossils became hugely empowered but also much criticized. I will not say here whether everything has been resolved. That is for the reader to consider at the end of chapter 14.

Among British workers, my main contact has been Dick Aldridge. He gave me, at the outset of my research, the manuscript of a popular account of his scientific work on the animal that he had prepared for publication. Much of this was subsequently dissected by him and turned into papers that have reflected on the scientific investigation of the animals. The presence of Dick's account, with its focus on recent scientific developments and his personal program of research, encouraged me to write instead a long history of conodont research and develop a rather different approach to the discovery of the animal. Dick also gave me unhindered access to the library of conodont papers held by the Geology Department at the University of Leicester and the uncurated and uncensored correspondence between himself, Derek Briggs, Euan Clarkson, and others around the time of the animal's discovery. The manner in which these three men published the first description of the animal, their early ideas, and the criticisms made by friends are there for the reader to see. Dick was among those who read the whole manuscript, though he did so in first draft and not as it appears now. Interestingly, nearly all his comments concerned my use of English; he made no attempt to alter what I had written. My first words of thanks, then, must go to Dick. All readers of the manuscript have been equally generous. Maurits Lindström, who never saw the finished book, expressed it perfectly: “It is your book, write it as you like!”

The Great Fossil Enigma

The Great Fossil Enigma